Behind every unearthed cemetery, settlement, or outstanding find, there is a story to be reconstructed through meticulous observation and correct interpretation. We always seek for such stories. The fate of every human is, at the same time, an imprint of the era they live in, and individual stories are our only chance to understand the conception and beliefs of the peoples of a past era. However, the work is particularly challenging when there are no written sources to rely on.

In such cases, knowledge may only be gained by analysing the artefacts discovered and their find contexts - a source often less biased than written ones. By continuously searching for persisting evidence in an Early Avar cemetery and unceasingly working on decoding the information hidden in what has already been found, one may get a chance to reconstruct even more of the story. The puzzle becomes more and more complete during the investigation, outlining human fates, infinitesimal elements of the history of the world.

Burial grounds are sacred spaces, where the living become connected to a higher plane of timeless existence by the presence of a long line of ancestors. Neither can exist without the other: the one without roots is easily blown away by the wind, and the cemetery without ones remembering the dead disappears gradually from the face of the earth. But underground, even forgotten cemeteries keep the traces of bygone communities. Cemeteries are also silent witnesses to human fates and tragedies and venues of events; these stories, if one can decipher them, tell a lot about both the interred and the ones mourning them. The remains of offerings for the dead, and the other objects found in graves tell tales about the people who once lived there, while the bones of the deceased reveal details about their life, customs, and the diseases they suffered from.

Based on the remains of the villa unearthed there, the surroundings of Babarc in Baranya County, South-west Transdanubia in the Carpathian Basin, were inhabited already in the Roman Period - and life did not cease there in the following Migration Period either.

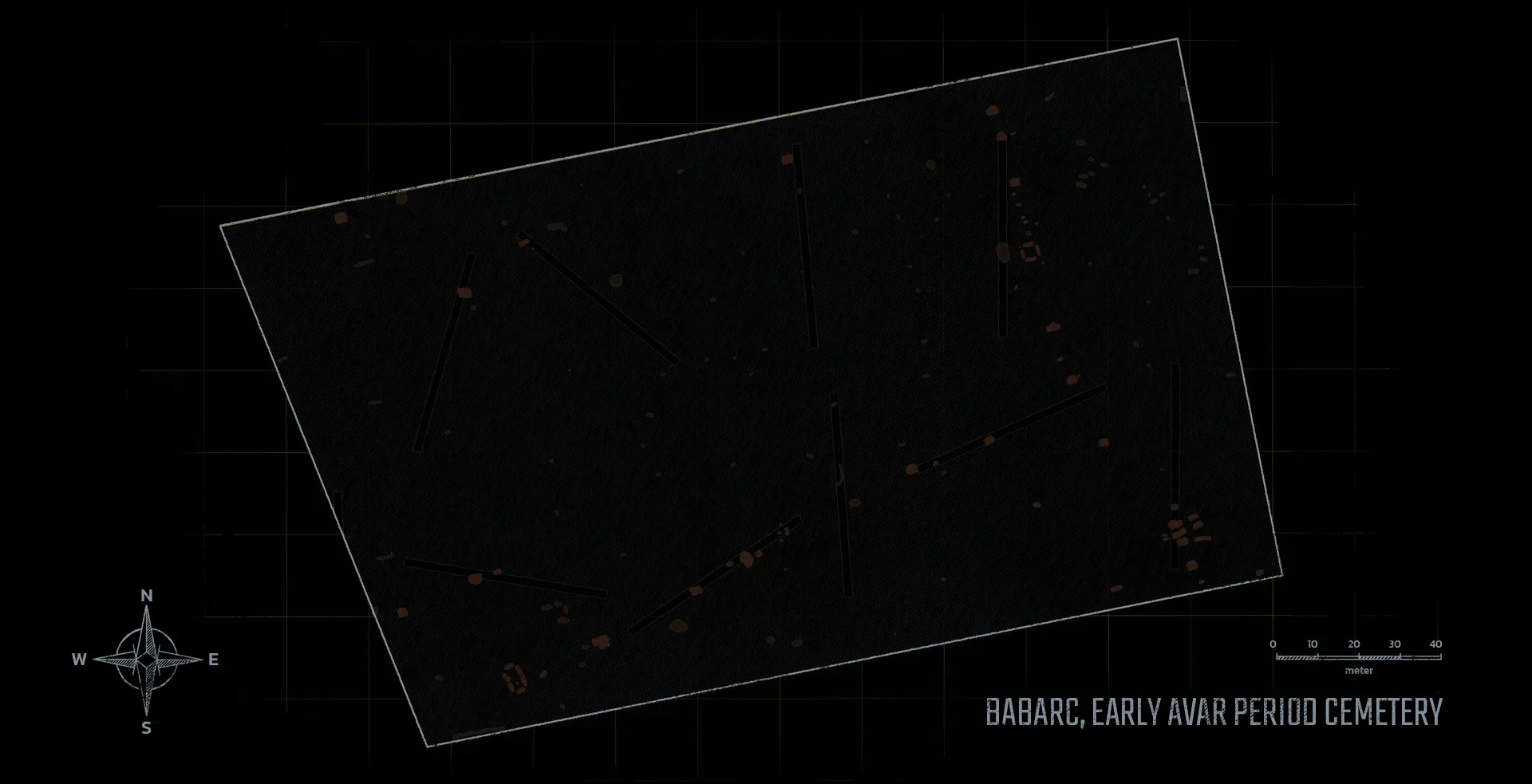

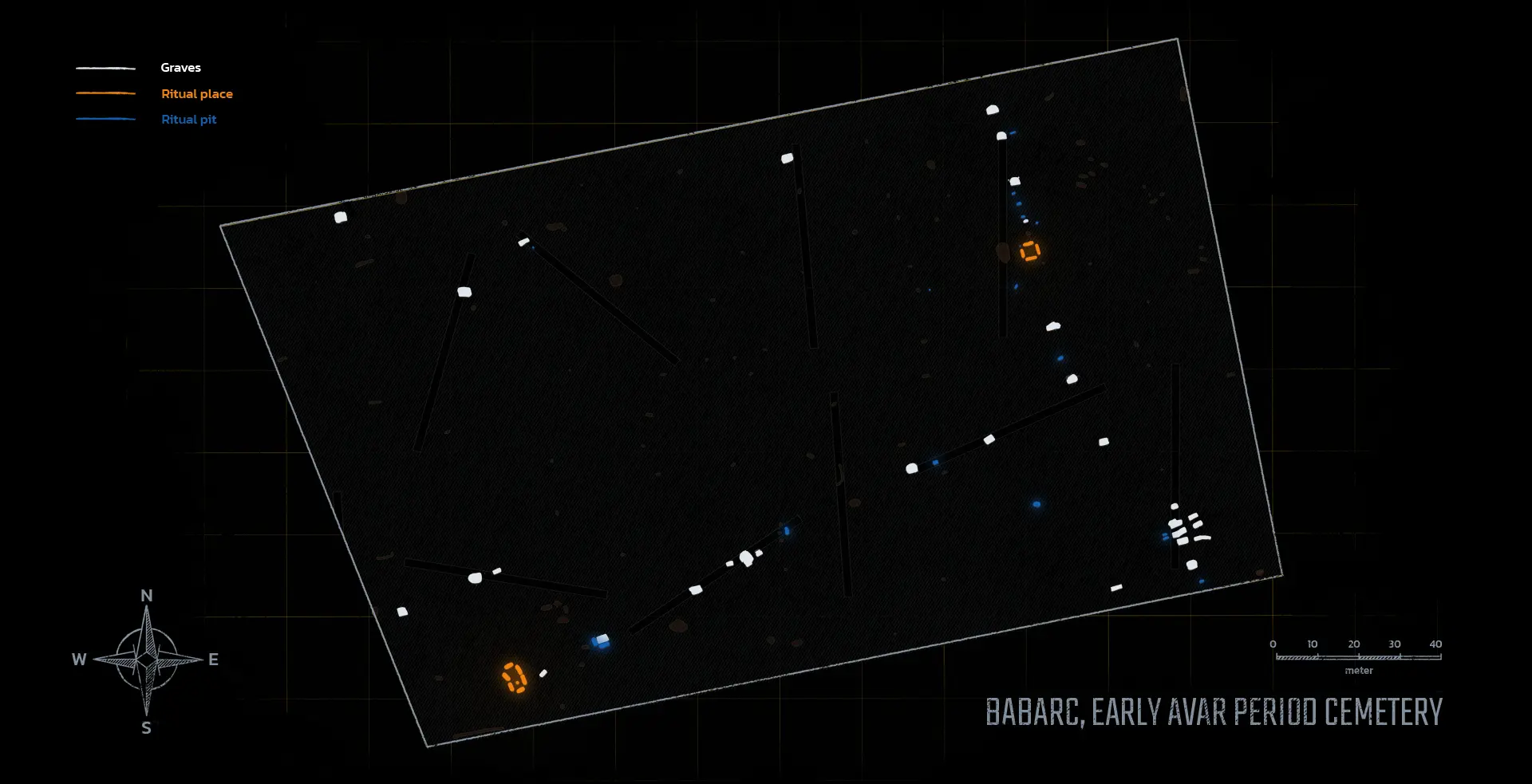

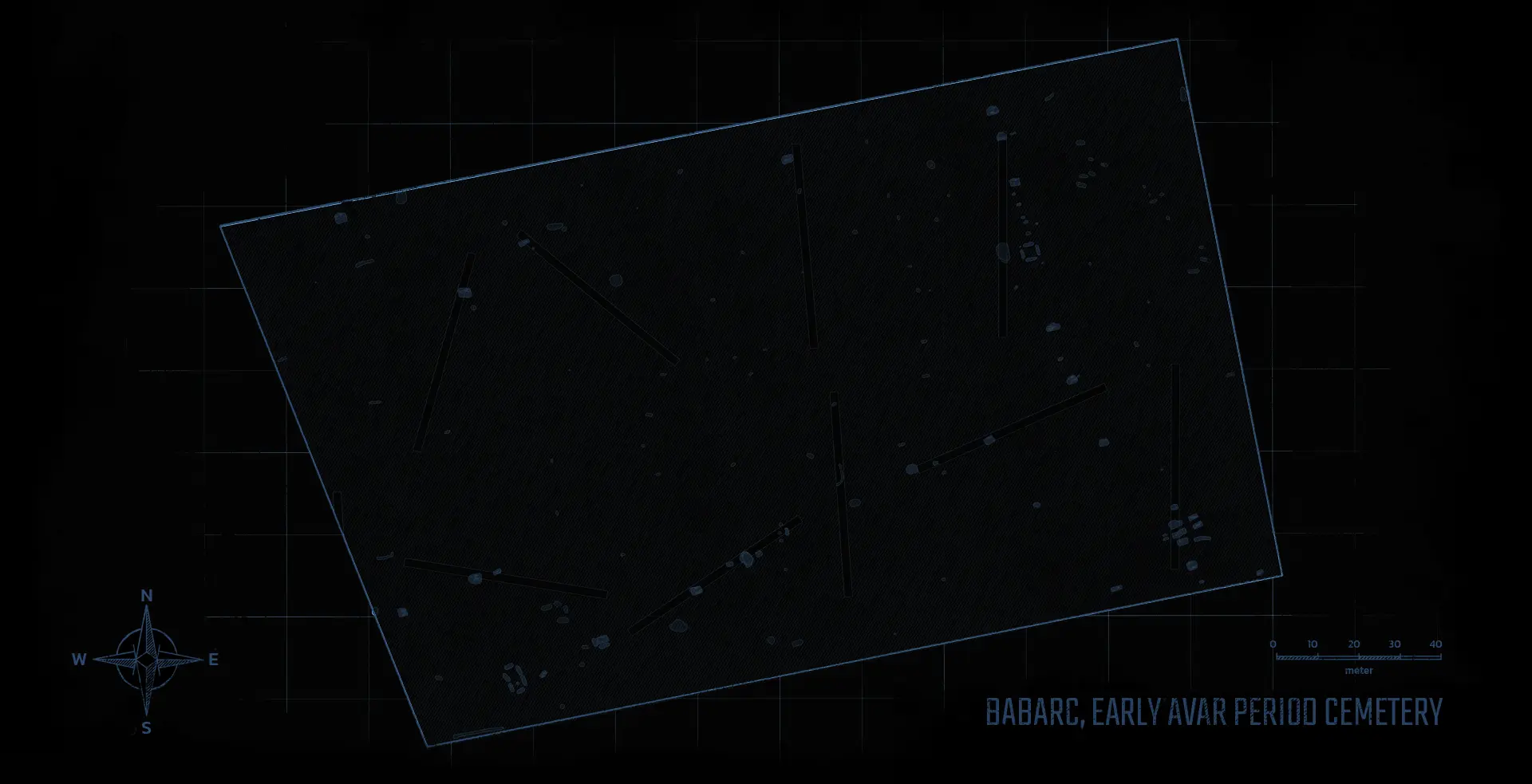

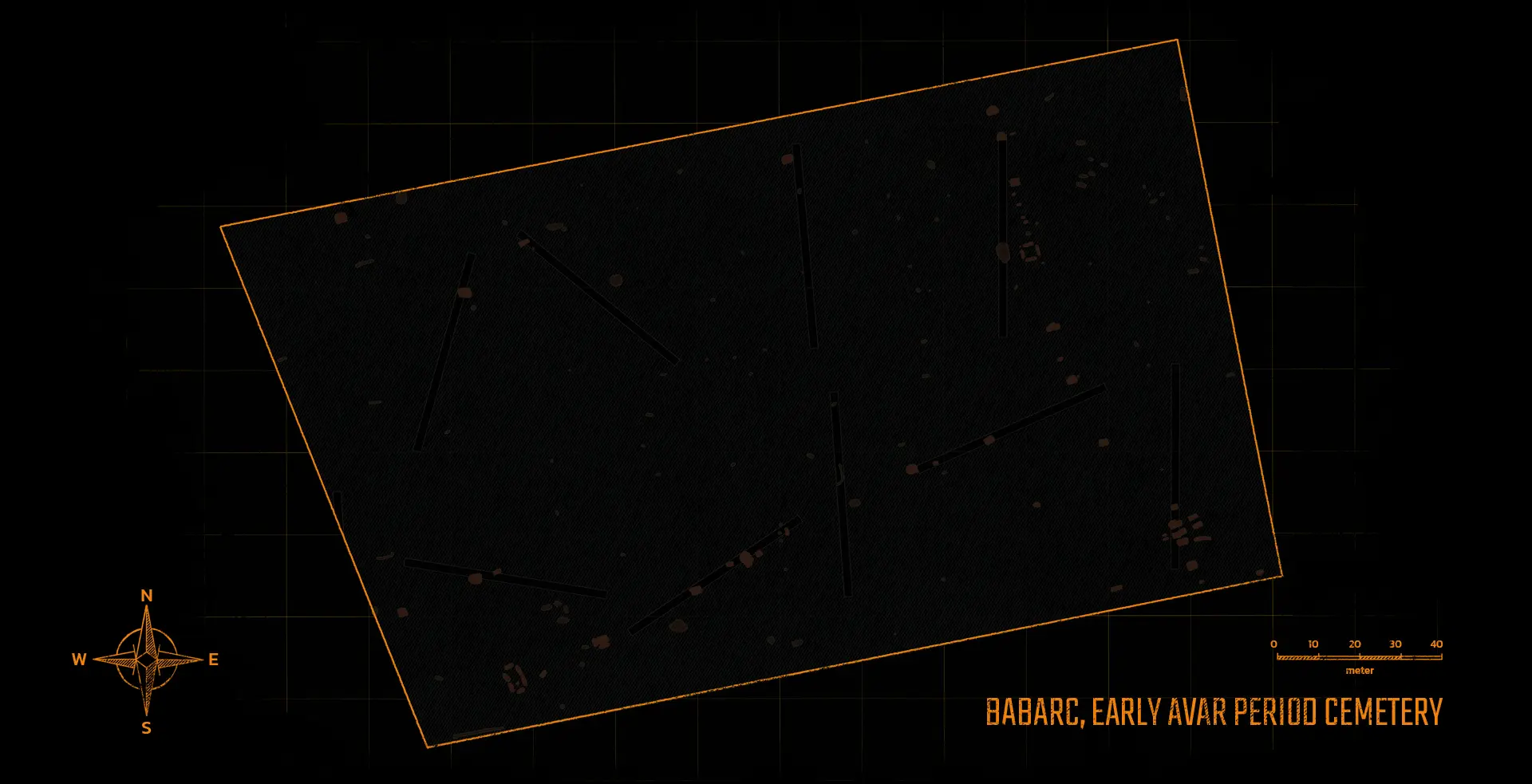

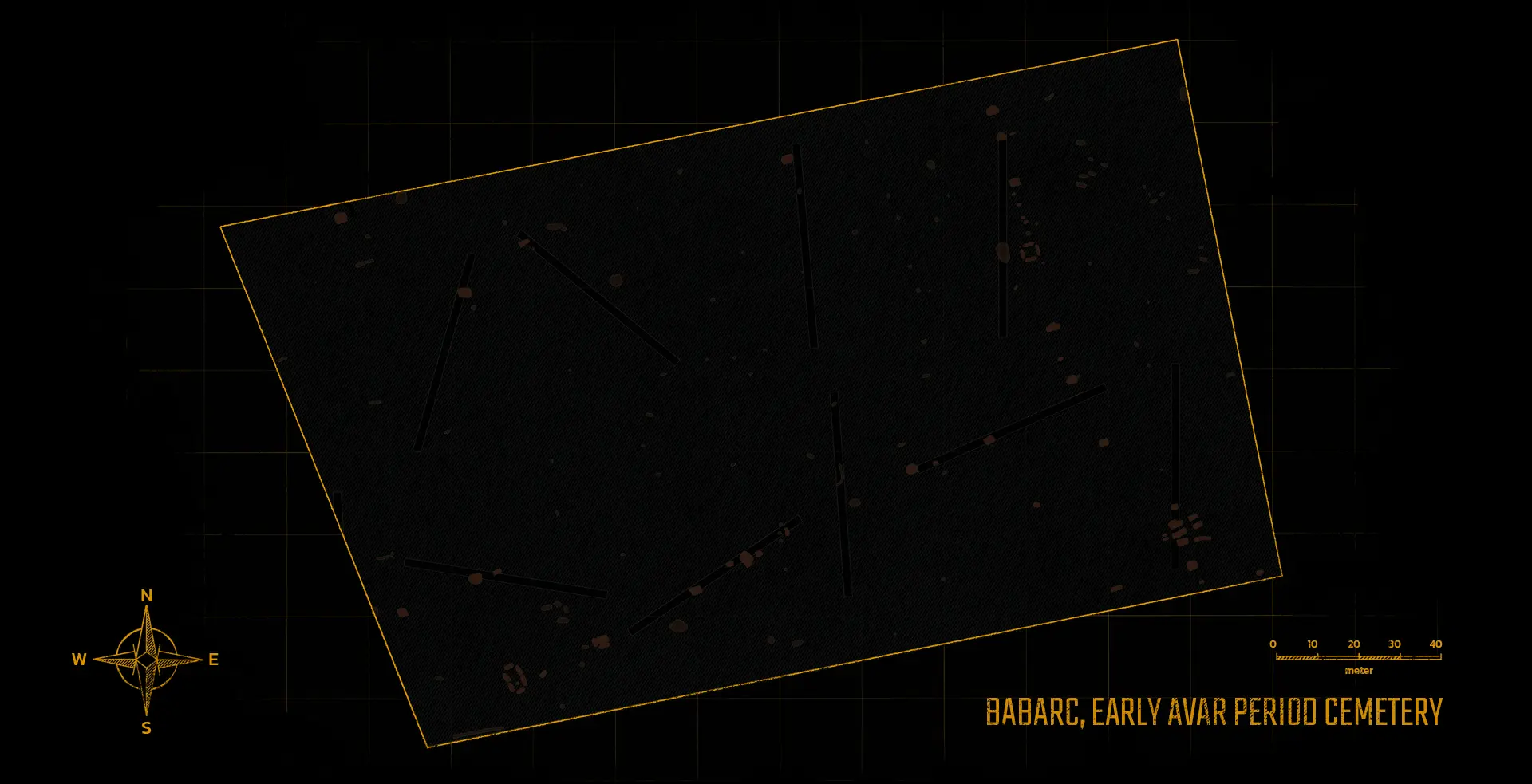

The teams of the Janus Pannonius Museum in Pécs and the Ásatárs Ltd. conducted excavations in 2020–2021 near the village of Babarc, unearthing an area of three hectares in the path of a planned motorway. Albeit many of them had considerable field experience, the discovered site astonished even the archaeologists participating in this project: the 44 graves and 25 ritual phenomena from the 7th century AD opened a window to an entirely new world.

Our knowledge of the Avars, a people invading the Carpathian Basin in AD 568 and replacing the Longobards who moved towards Western Europe, has been rather sketchy.

Byzantine and Western sources outline a mighty nomadic empire that tore down the centuries-old geopolitical structures of the Balkans, conquered Thessaloniki, and joined its army with that of the Sasanid Empire to siege Constantinople, the heart of the Roman Empire, in AD 626.

But we have no written sources from inside the Avar Khaganate. In lack of them, we only have the cemeteries to reveal details of the life of the Avars and the two-and-a-half-centuries of history of their horse-nomadic empire until the early 9th century AD when Charlemagne led consecutive campaigns against the Khaganate and destroyed it. Based on the record of the cemeteries, the extended multi-cultural connection network that had linked the peoples of the Avar Khaganate to the East and the Byzantine Empire in the eastern part of the Mediterranean - a network similar to what had existed already in the Roman Period - was certainly maintained until at least the end of the 7th century AD.

Compared to other coeval cemeteries in the Carpathian Basin, the one unearthed near Babarc is extraordinary in many respects. First, the deceased were unusually lavishly furnished for the afterlife: their graves contained numerous gold and silver jewellery items, precious weapons, and many Byzantine coins.

Most of the wealth was obtained as spoils in wars fought with neighbouring peoples, while shrewd people could also accumulate considerable fortunes from trade with countries in the east, west, and south.

Precious metal items were resold to buy luxury and everyday items and weapons or kept and worn as amulets or marks of social status.

While Avar cemeteries rich in grave finds have also been discovered elsewhere, the one unearthed in Babarc excels among them, attesting to the one-time presence of a special group in the area.

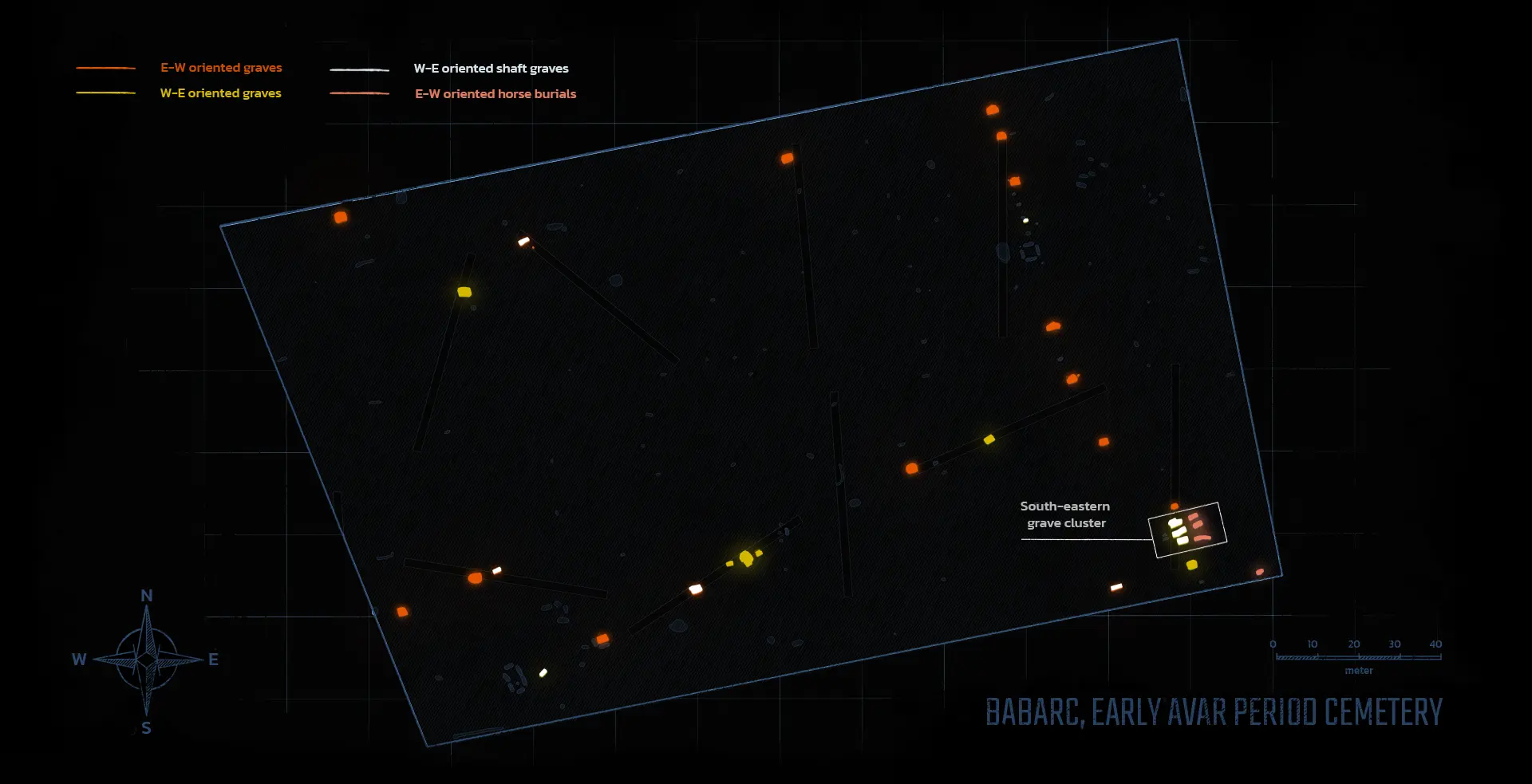

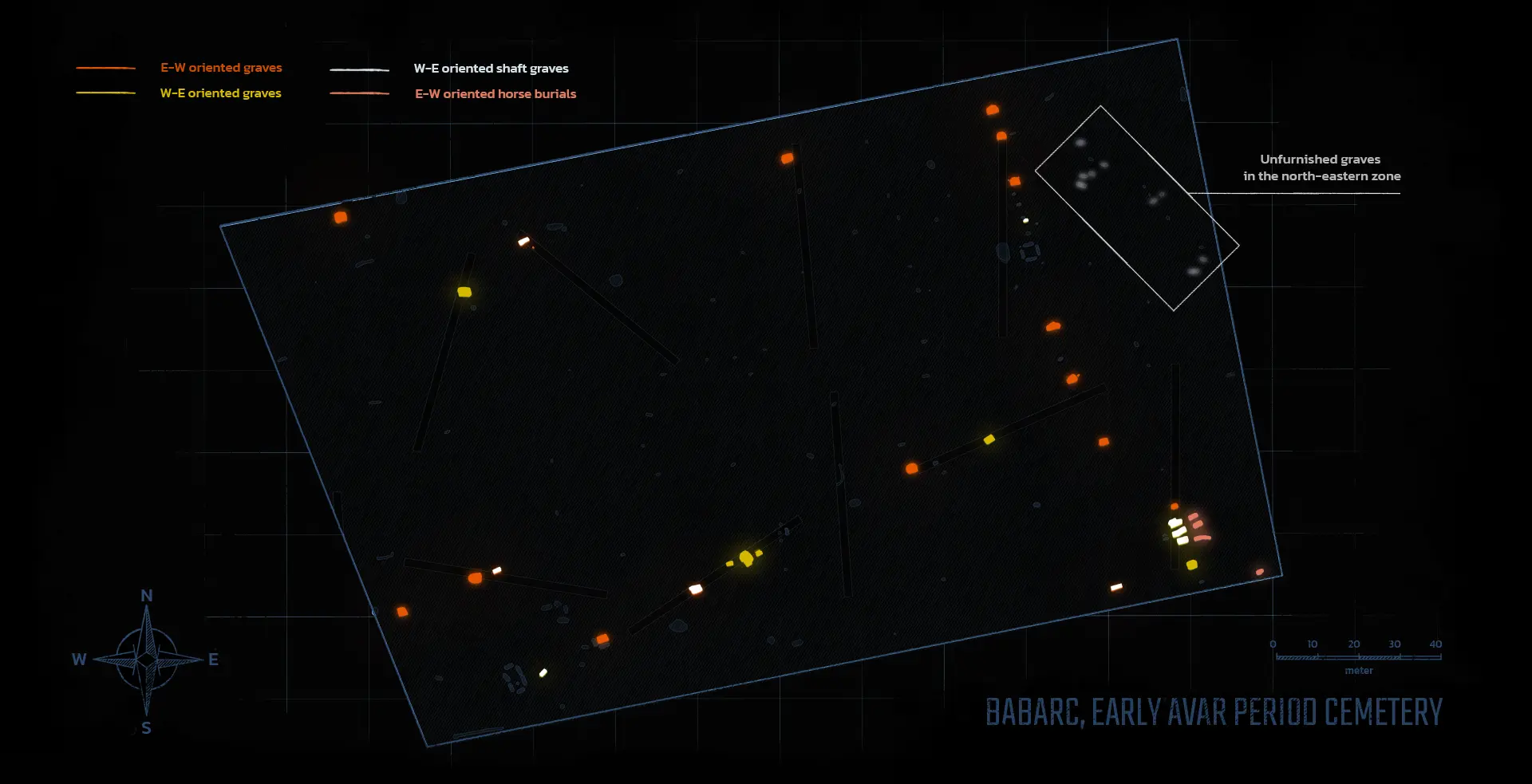

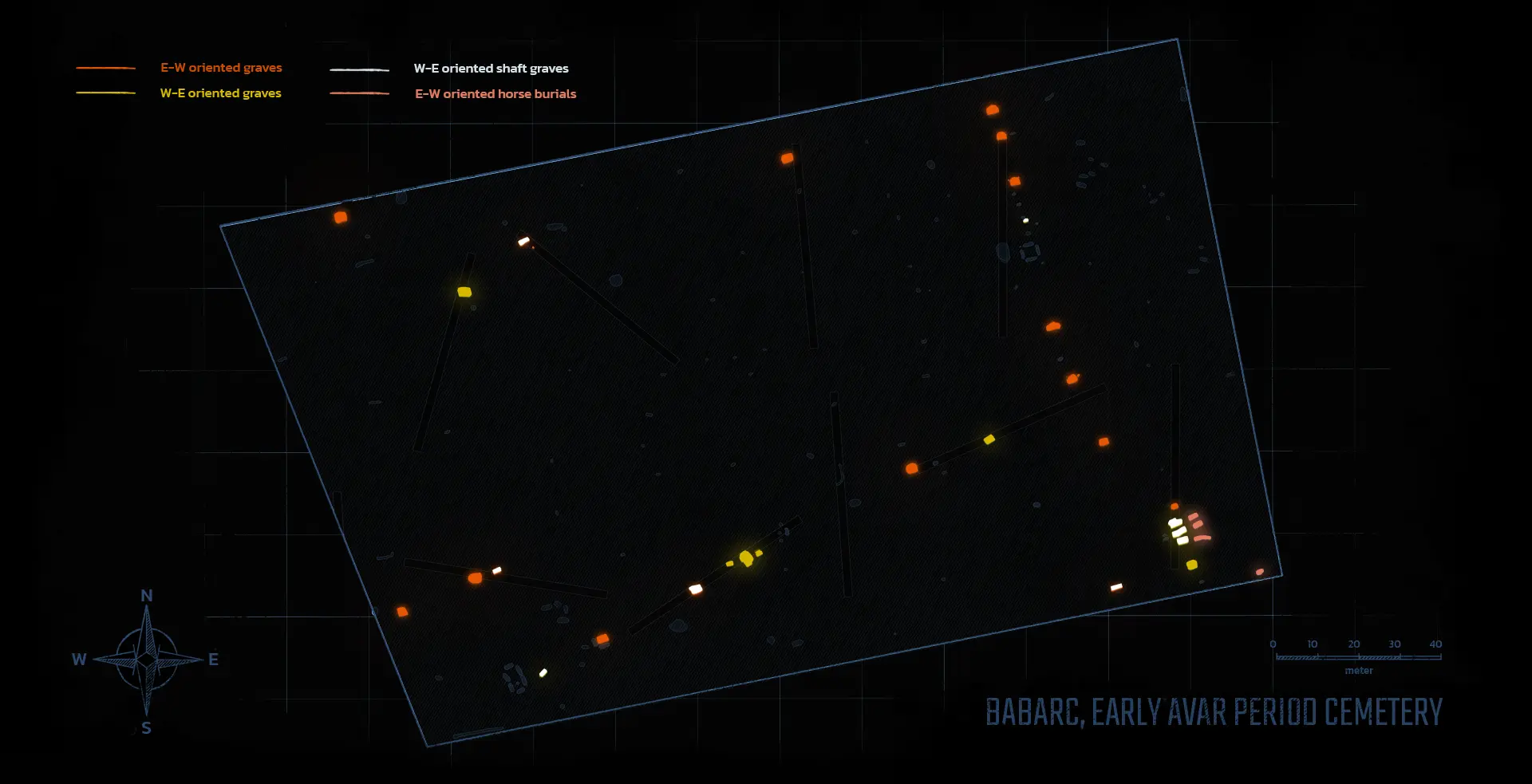

Lack of order is a characteristic of this cemetery, where not even the germs of the usual grave rows appear. It consists of lonely graves and smaller and larger grave clusters, sometimes fifty metres away. Only genetic analyses may reveal whether it belonged to a family or kin.

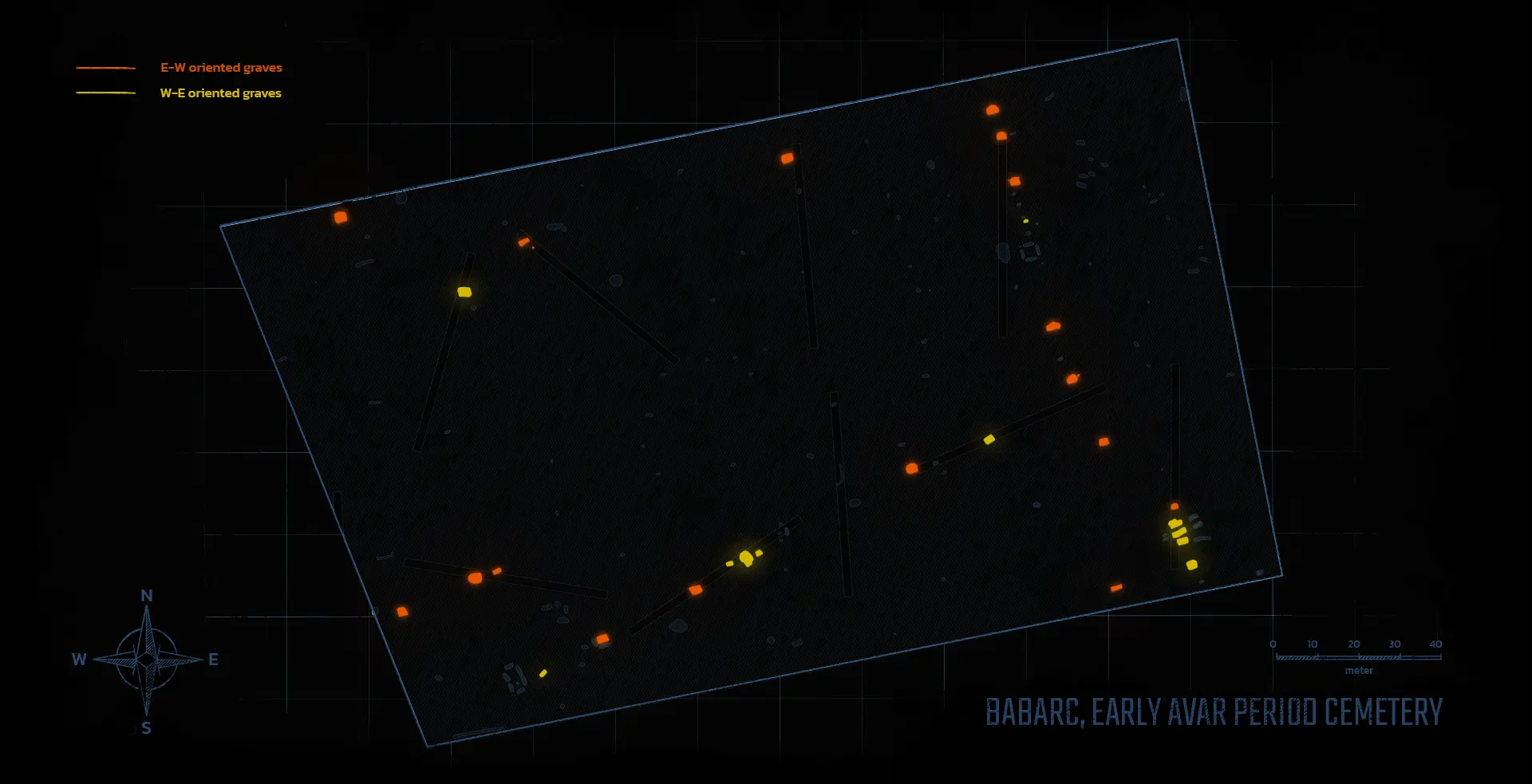

Two-thirds of the graves are more-or-less east-west directed, while the orientation of the rest is the opposite, west-east.

A small grave cluster in the south-eastern part of the excavation area is clearly distinct from the rest of the cemetery because of the opposite, west-east orientation of the graves and the three east-west oriented individual horse graves east of them.

Some unfurnished west-east oriented graves in the north-eastern zone of the excavation area also formed a cluster. These, being the remnants of previous historical eras, are not related to the Avar Period.

There are regional differences in the orientation of the Early Avar Period graves. Their evidence alone, however, is insufficient for drawing conclusions about the cultural ties of the related communities as, albeit in different proportions, similar patterns can also be observed in other coeval sites. That the main orientation in the nearby cemeteries at Kölked-Feketekapu was west/southwest-east/northeast is a clear mark of the significance of orientation as, while the Babarc community maintained trade connections with the people behind these cemeteries, their influence did not result in a change of grave orientation.

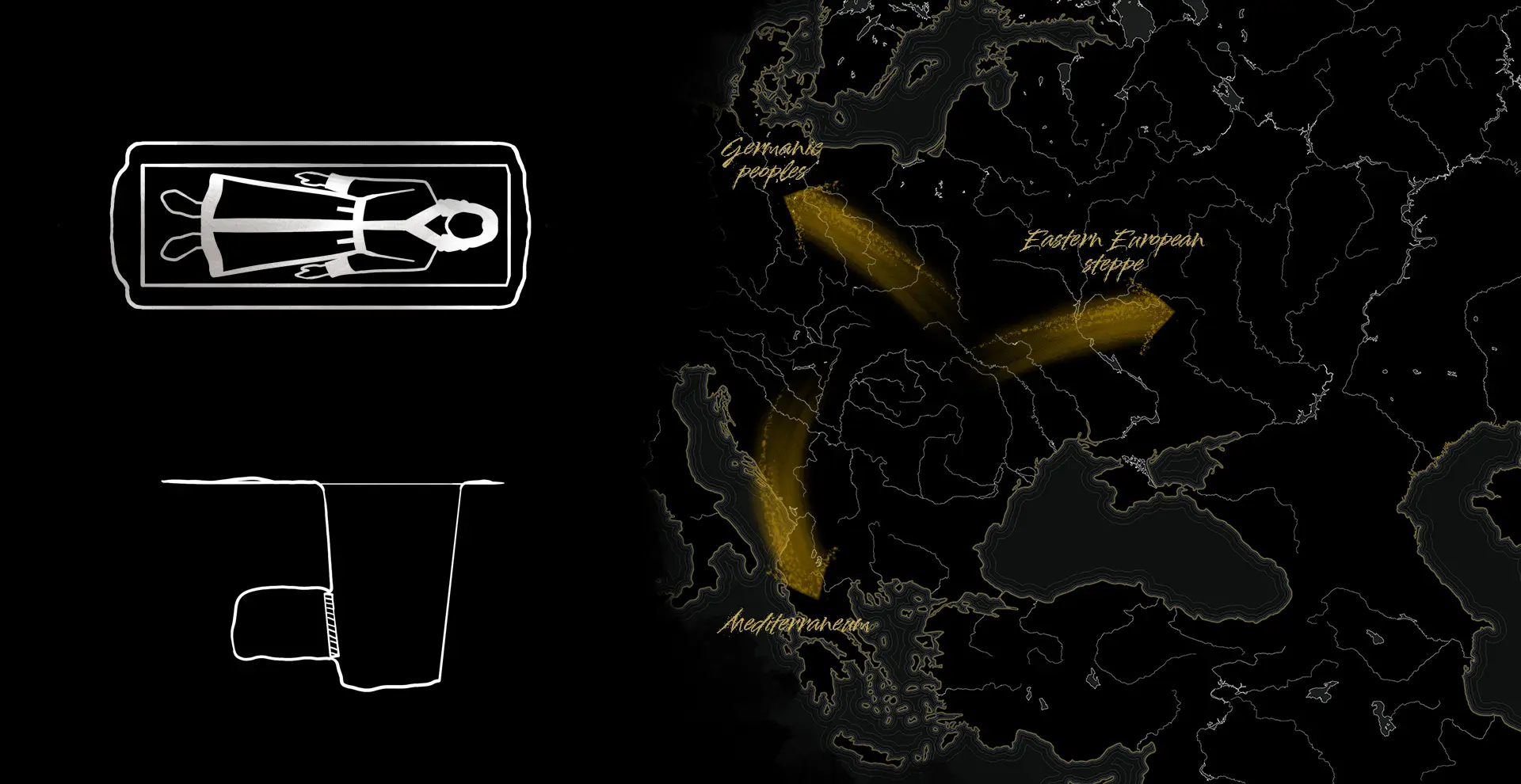

Based on the observed elements of the funerary rite, the related community does not fit the local pattern but can be linked with groups settled in the Trans-Tisza Region (more than a hundred kilometres away) and Eastern Europe.

These traits include the east-west orientation of the graves, the graves with a sidewall niche, the partial animal offerings, and the sheep rumps as food offerings. This complex phenomenon currently has no known coeval analogy in the Carpathian Basin, making it extremely difficult to find its proper place in our knowledge about the period.

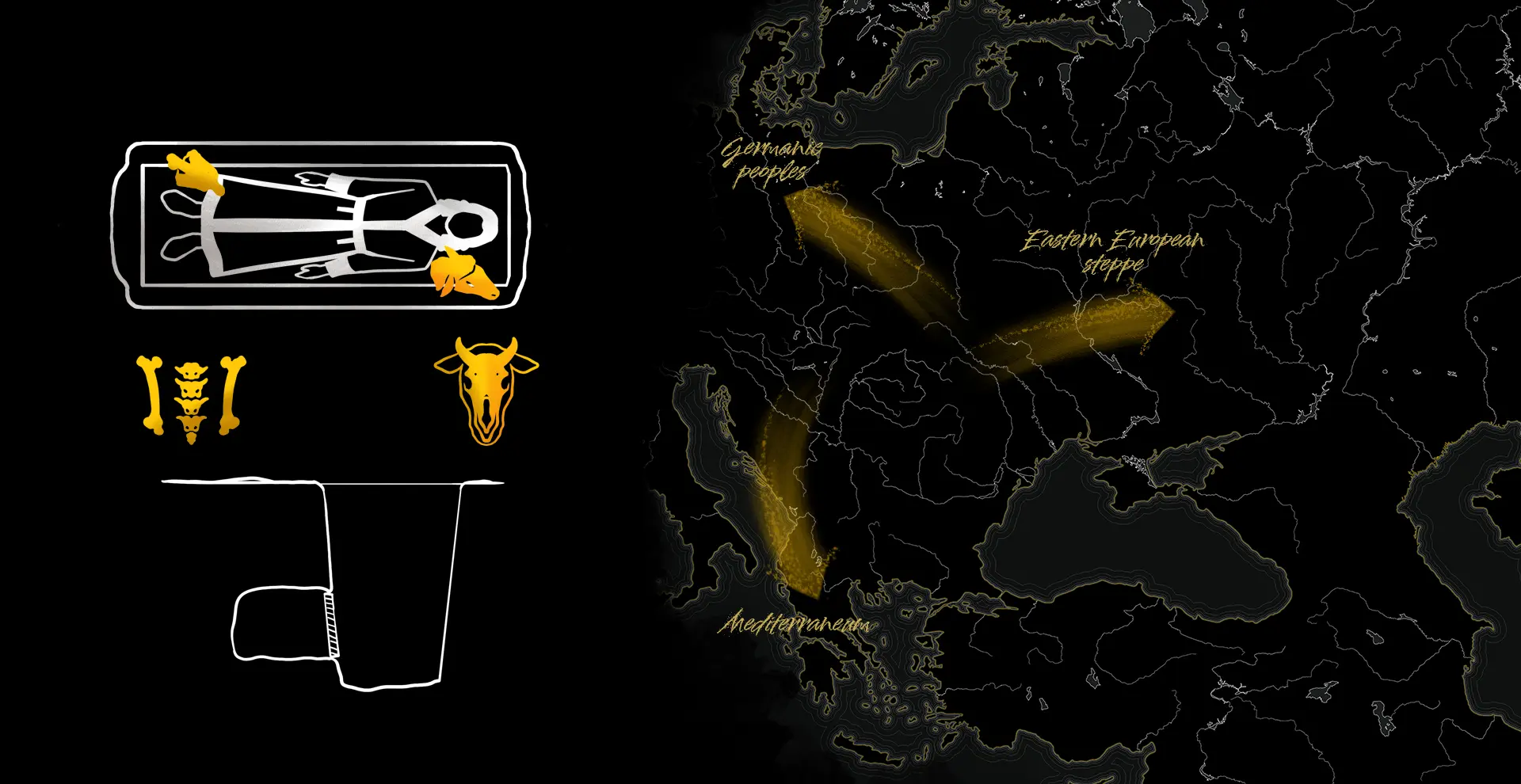

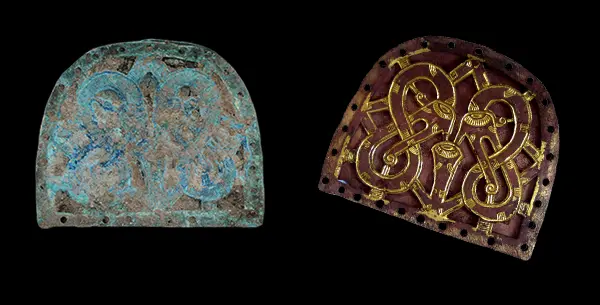

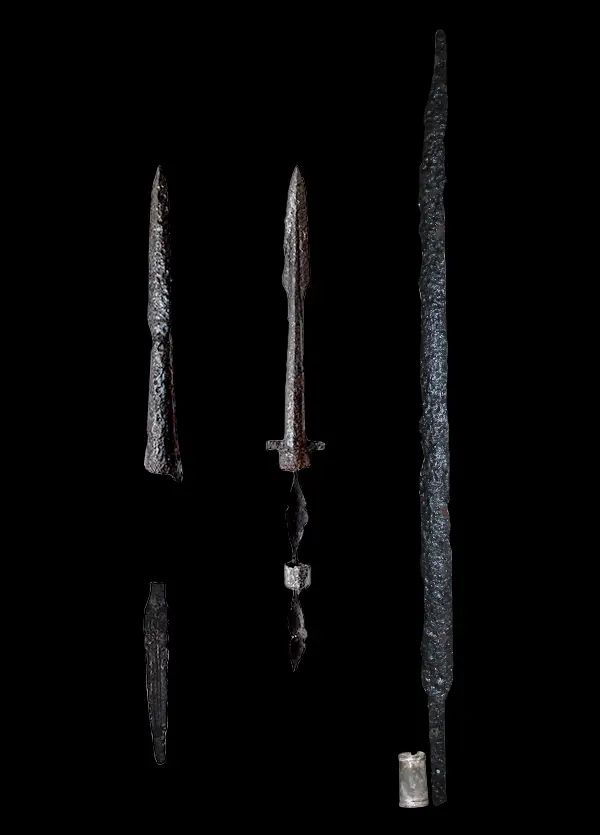

While the funerary rite links the mortuary community of the Babarc cemetery with the steppe zone in Eastern Europe, the jewellery items recovered from the graves mark out their connections with the Mediterranean, and some weapons - the quiver mount and the winged spear - are Germanic types. Conclusively, cultural influence reached the Babarc community from at least three separate directions.

The experts excavating the site were astonished upon discovering, besides the graves, ritual features that did not contain any human remains. These mainly consisted of shallow pits, each positioned seemingly with consideration to the others, which contained the remains of diverse objects. The ditches in two cases were part of a structure, four and six of them, respectively, surrounding an empty rectangular space.

The finds recovered from the fill of these pits only included types usually related to men and boys: arrowheads, gilded horse harness mounts, drinking vessels, and the fragments of a spouted jug. These places were possibly for remembering the warriors who had died far from home during a military campaign. The small ungulate bones and skulls, hand-formed pottery vessels and occasional eggshells and glass beads discovered in the small pits around the graves may be the remains of the offerings presented to the deceased.

Such a pit in the north-western part of the cemetery hid seven high-quality arrowheads, painted red for mysterious reasons, once interred in a wooden box fastened with iron nails.

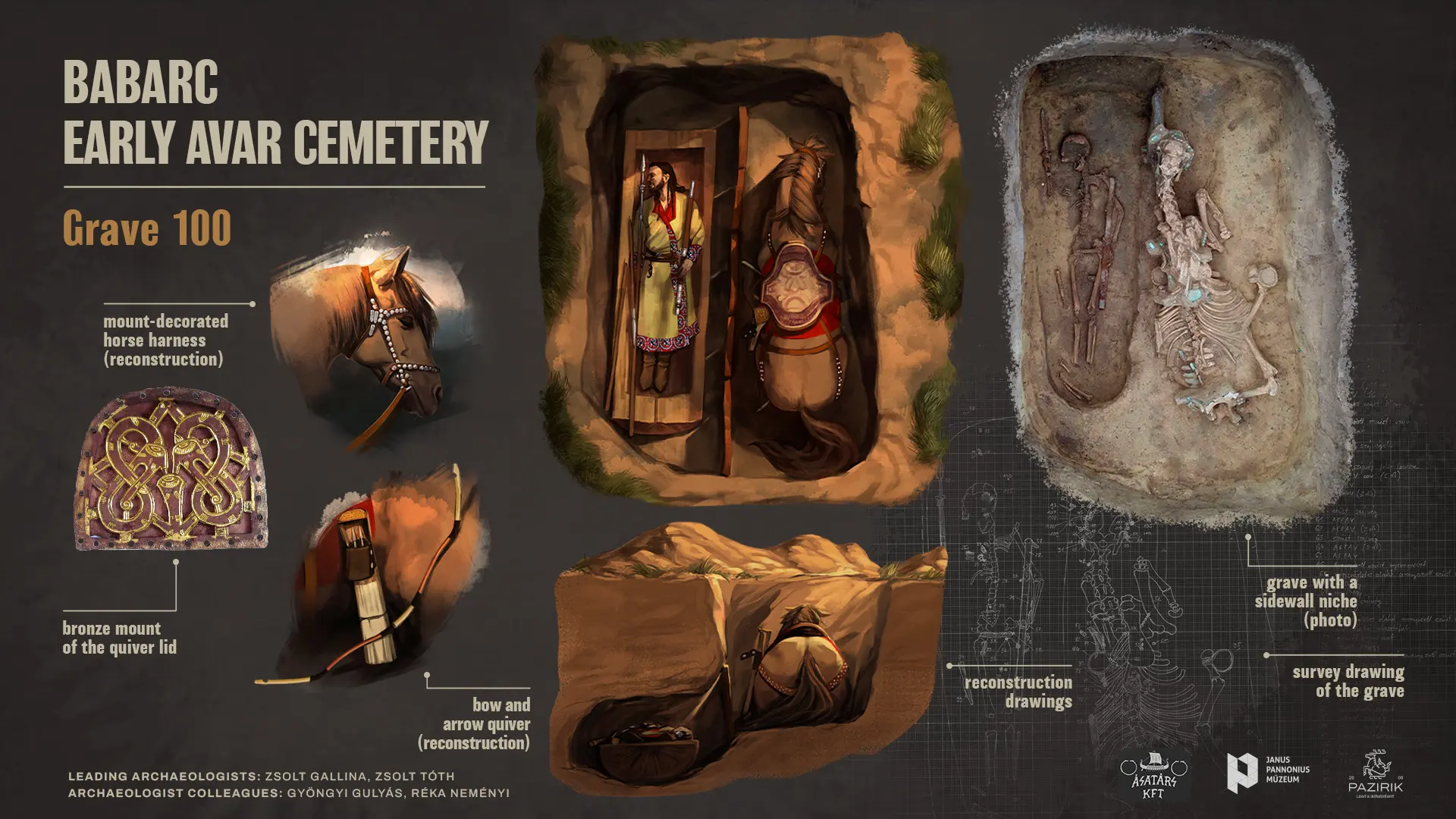

Grave 100, the final resting place of an Early Avar Period warrior, stands out even from the unusually rich archaeological record of the 44 graves and 25 ritual places on the site.

Nomadic people with a military lifestyle held their warriors in exceptionally high esteem; they often became the leaders of small communities. The cemeteries of warriors are always outstandigly rich, revealing a lot about the hierarchical Avar society.

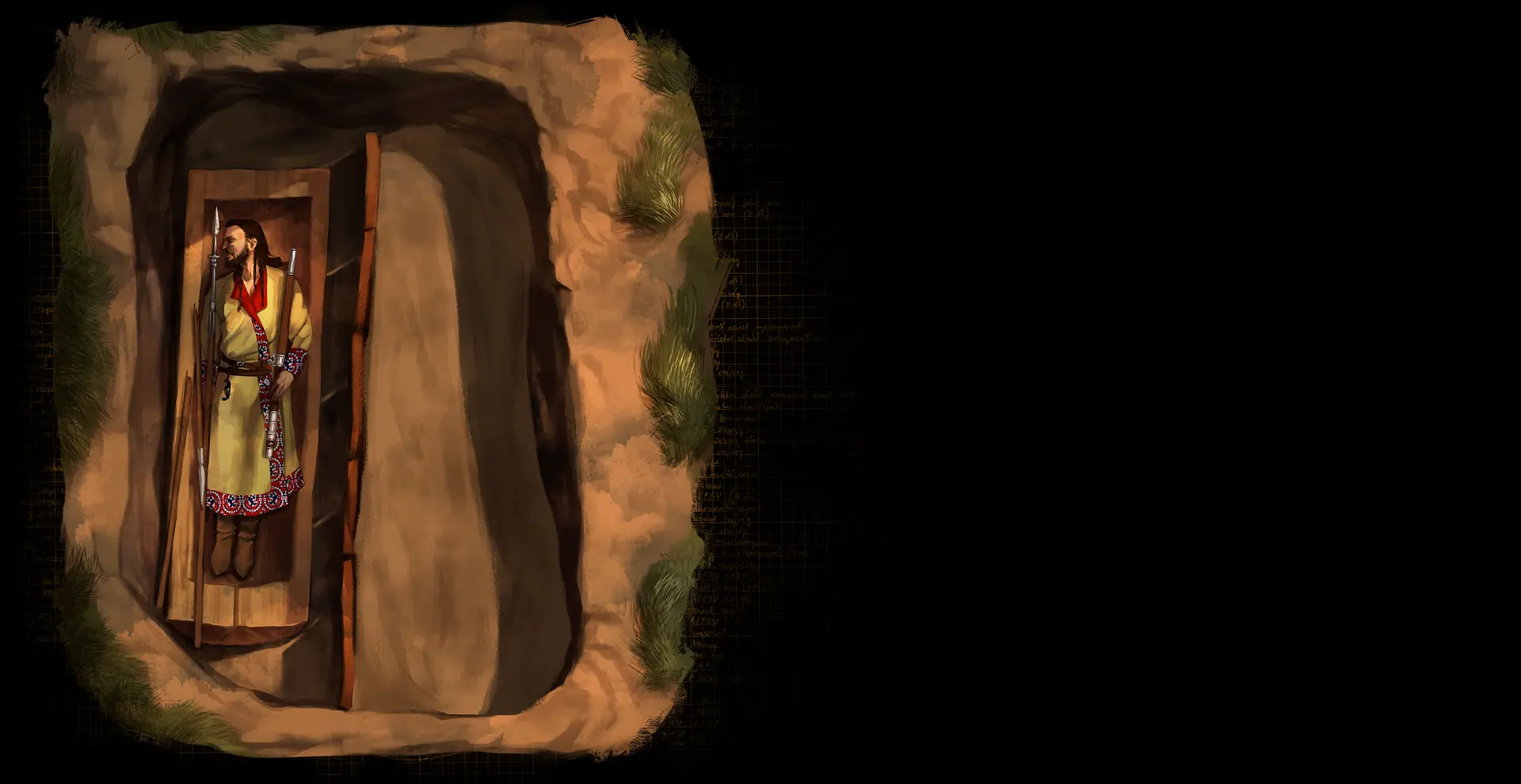

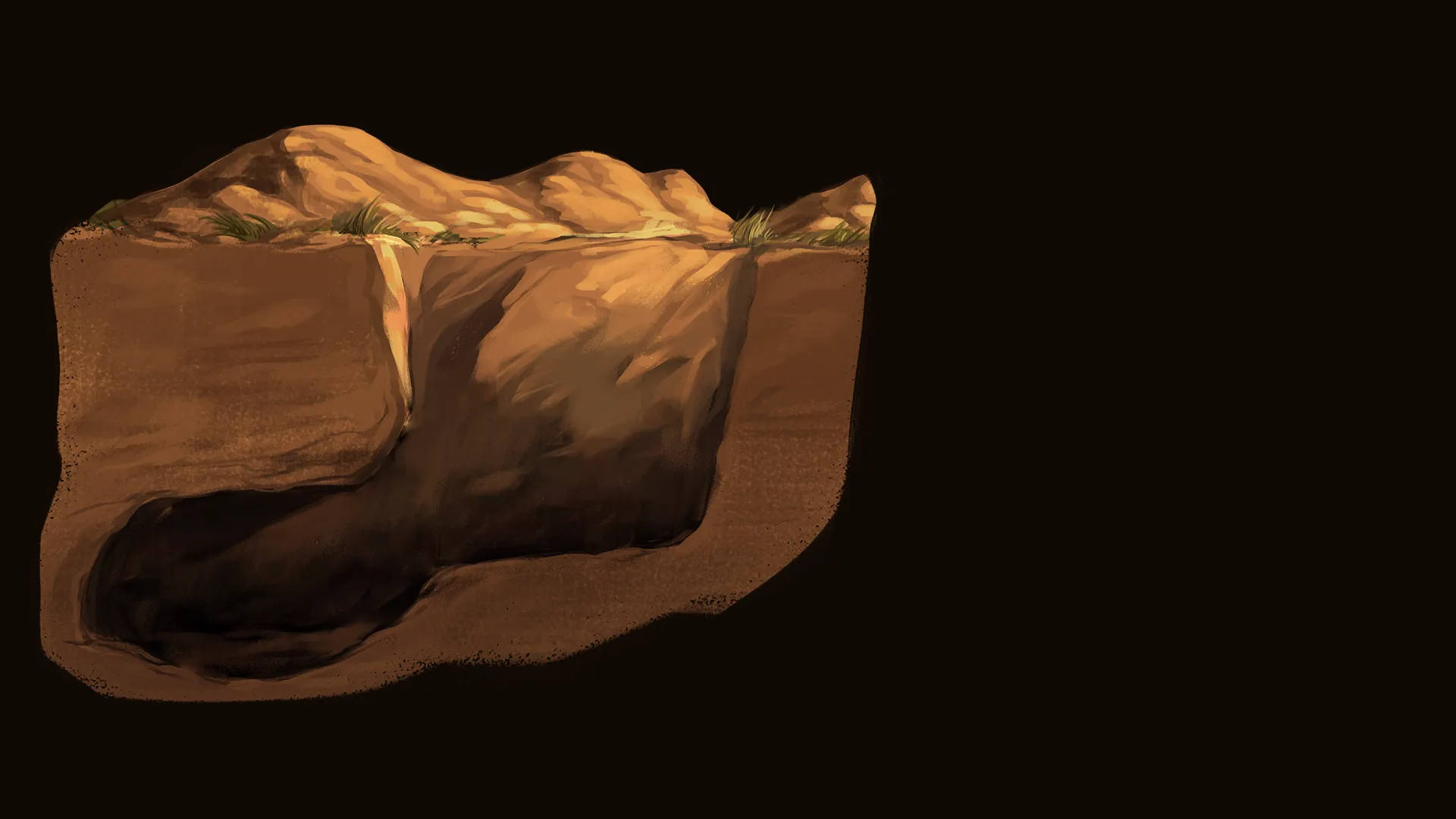

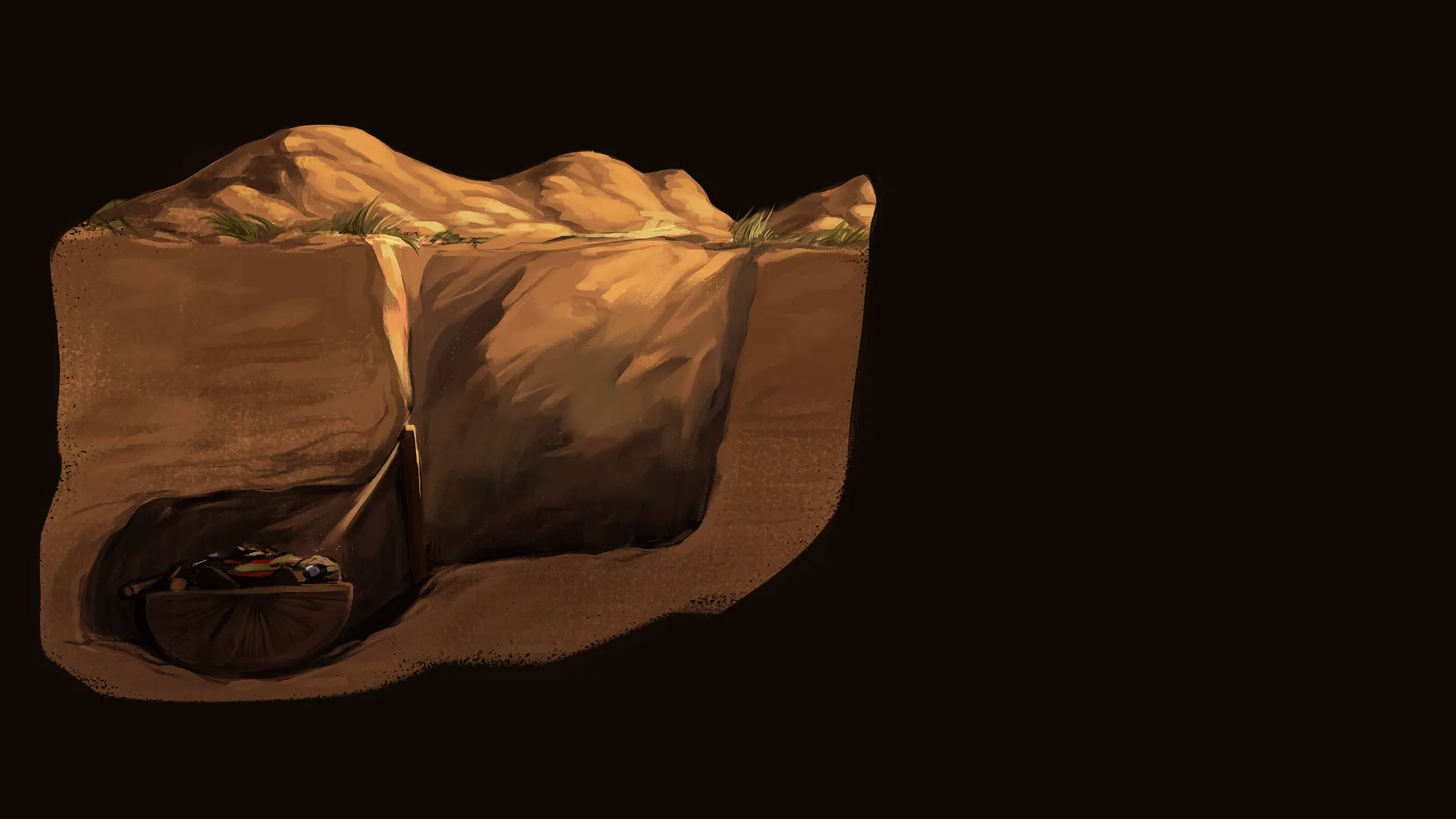

The man in Grave 100 had been cut off in his prime; he was laid to rest in a grave with a sidewall niche with his horse.

During the funeral, his coffin was lowered into the niche first...

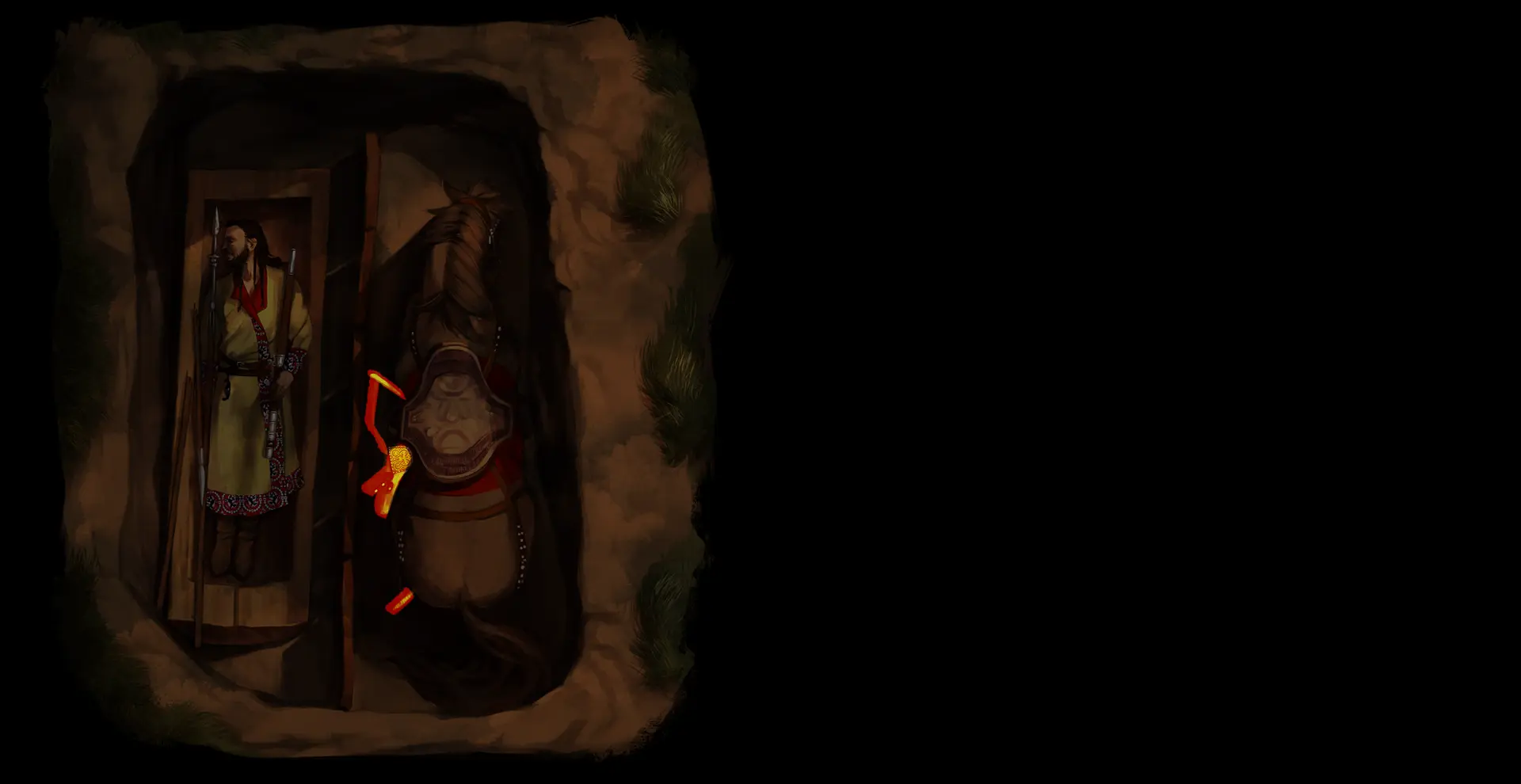

...and then the body of the previously killed horse, dressed in an ornate harness, was placed on the bottom of the main shaft of the grave pit.

The mourners placed the bow and the full arrow quiver to the back of the horse. The quiver was decorated with a mount with motifs of Germanic origin, the analogy to which is known from the nearby Kölked-Feketekapu.

The man was dressed in a kaftan for the burial; a spear broken in two and a hooked spear were found beside his remains. Based on the precious mounts recovered from the grave, he must have been a leader of the local community.

As the word ‘padmaly' is no longer used, it is undoubtedly worth explaining [the grave type is called 'padmalyos sír' in Hungarian, which translates to 'a grave with padmaly’]. The word is of Slavic origin; it means the small cavity dug into the side of streams where the fishes could come out to rest - the related fishing method, catching the resting fishes from these cavities, was called padmalyozás [ca. padmalying, cavity-ing].

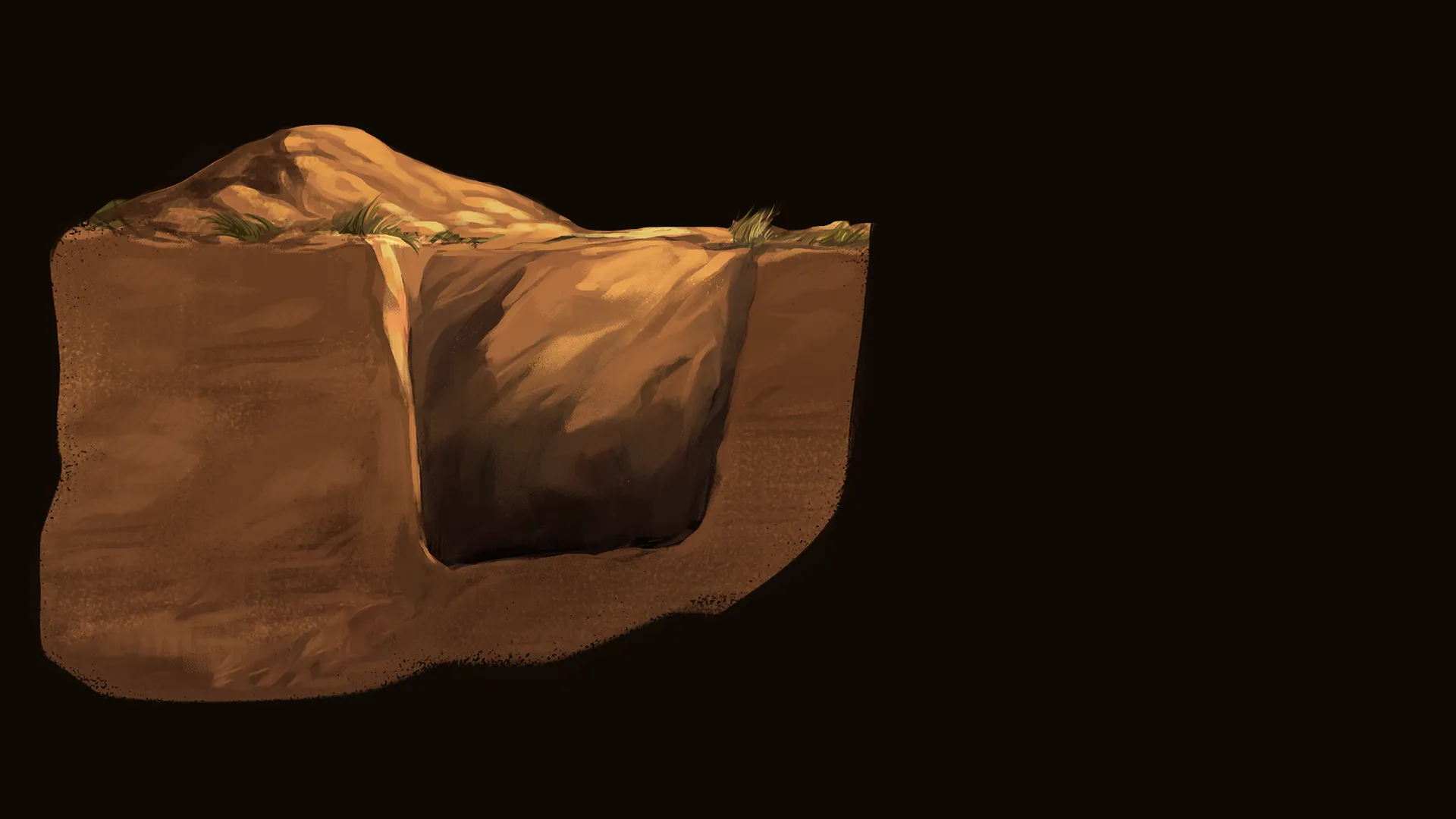

The same word has been used to refer to the elongated niches carved into the side of deep pits, mainly in cemeteries. With such graves, the main shaft was dug first (the place for the horse buried with the deceased)...

...and next, an elongated niche (the place for the deceased himself, a sort of earthen chamber where soil did not cover the coffin) was carved out of one of the sidewalls. During the funeral, first, the coffin was put in its final place, and then the horse was lowered into the main shaft.

According to the common belief, nomadic warriors were always buried with their horses, the animal lying in the grave prone. As this custom in the Avar Period was popular mainly in Transdanubia, there is a possibility that it is an adapted Germanic (Merovingian) element inherited from Langobards, a people inhabiting these lands beforehand. In many cases, the spearheads have also been found next to the horse, indicating that early Avars linked this weapon with the horse instead of the warrior.

However, not the complete body of every horse was buried with its owner: sometimes only the skull and the leg bones, still in the folded hide, were placed to the left side of the deceased. This partial horse offering was also in practice in Babarc. Each grave contained only a single horse, the remains of which were placed in the grave with an orientation matching that of the owner. While some horses were not harnessed for the burial, usually the bit, the stirrups, and the metal accessories of the headgear and the breeching are amongst the finds of such graves. In the case of a partial horse burial, the saddle was placed on the shins of the deceased.

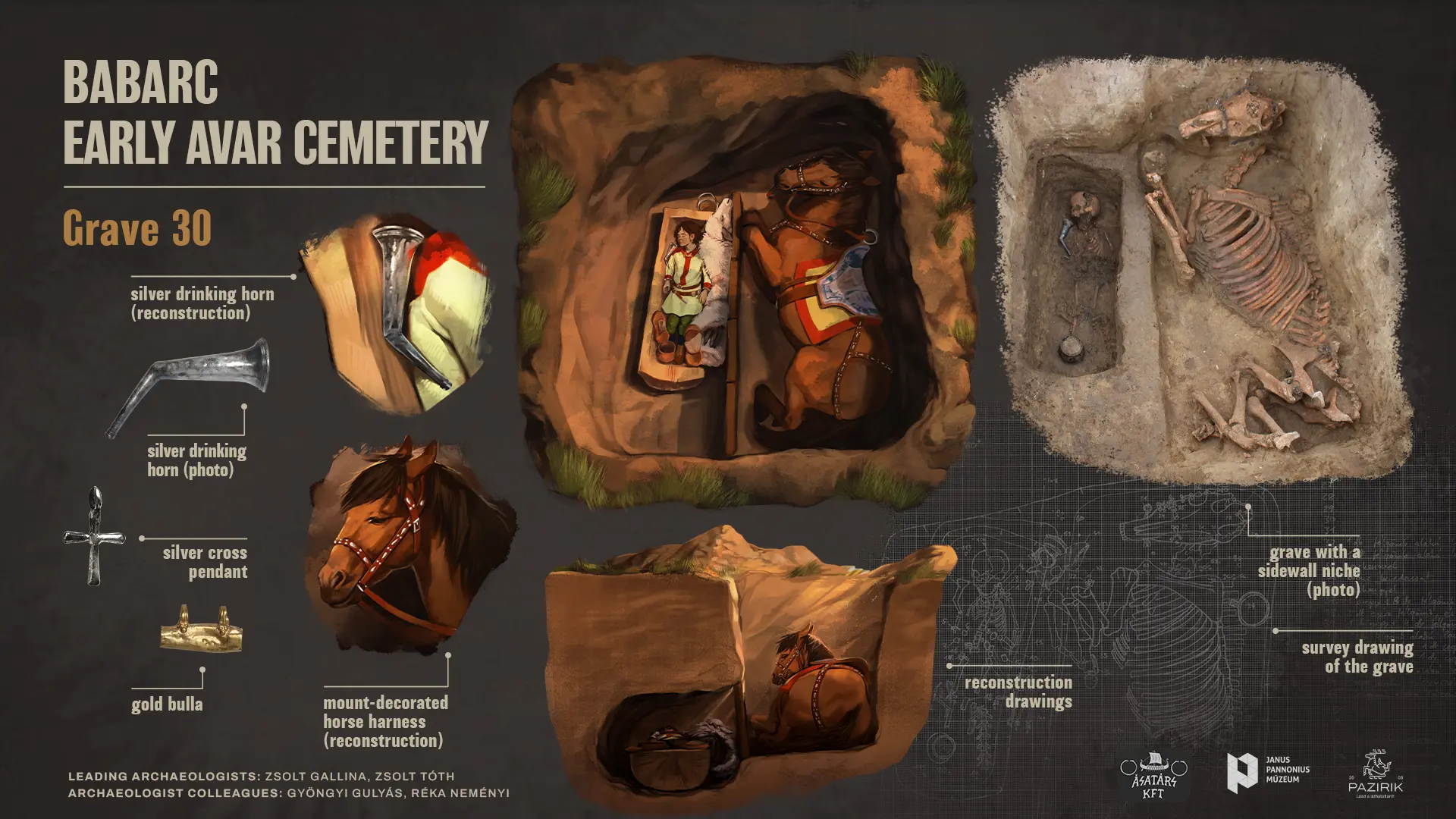

Grave 30 is extraordinary in every imaginable respect and has provided considerable new data on the relations inside the family and between parents and children. This grave is of a child buried with his horse, in a way befitting adults.

His coffin was covered with the skin of the lamb served on the funerary feast. He was dressed in Mediterranean-style clothing and provided abundant food so he would not be short of anything in the afterlife. The mourners also placed a wooden bucket decorated with metal mounts and a sheep’s skull above his head.

The anthropological analysis of his remains revealed that the child had probably suffered from some severe illness. His parents must have done everything they could to get him healed, as attested by the amulets about his body: a silver cross, a gold bulla, and a bronze axe-shaped pendant worn in his neck. These suggest that the parents kept with the universal pattern in trying to turn every stone and seeking the help of every god they could think of to make him healthy again.

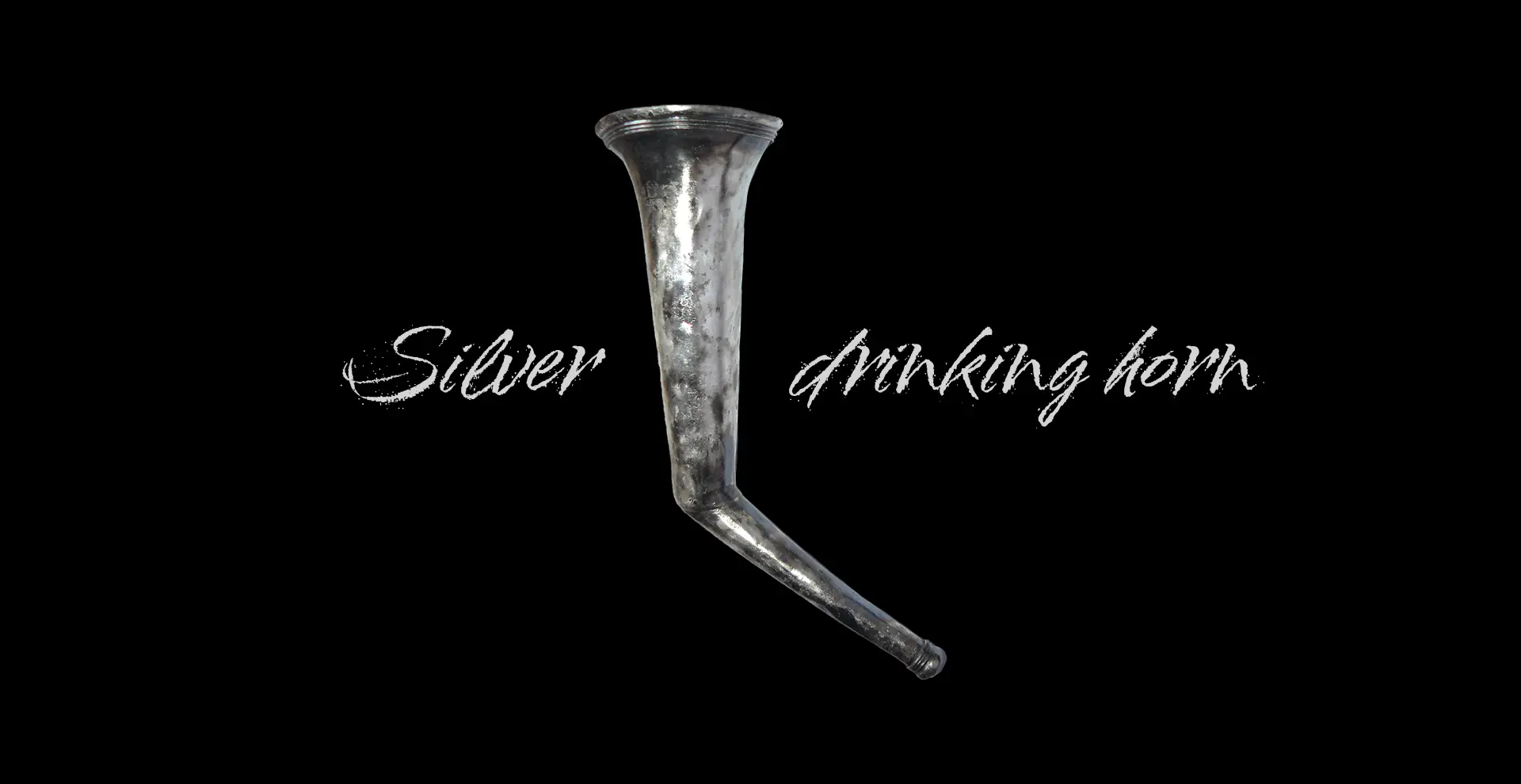

The child, merely one- or two-and-a-half-year-old at death, was a distinguished member of his community. His prominent position in society is also marked by the silver drinking horn placed next to his right shoulder. Such items are exceptionally rare in graves; the closest analogy to this find is known from the burial of the Avar prince in Kunbábony.

The community settled in Babarc abandoned their dwellings in the mid-7th century AD and, thus, vanished from before our eyes for good. The 'semi-finished' cemetery suggests that they probably left in a relative hurry.

The cemetery, discovered after a millennium and a half, reflects a community with an extended connection network, the members of which somewhat differed from their neighbours. Without written sources, only their dead are here for us to help revealing some details of their one-time life.

ExpertsJózsef Zsolt GALLINA, Bence GULYÁS, Gyöngyi GULYÁS,

Flórián HARANGI, János MESTELLÉR

SynopsisAndrás BALOGH

ScriptAndrás BALOGH, Szabolcs VARGA

IllustrationsGábor EPERJESI, Dóra Kata JAKOBOVICS

DesignRebeka KÖVES

English versionKata SEBŐK

DeveloperZoltán RÓNOKI

PhotosTamás GÁL, Bálint KATONA

MusicShahead MOSTAFAFAR

ImagesÁsatárs Ltd. and Janus Pannonius Museum

2023

The excavation was conducted by the teams of the

Janus Pannonius Museum and Ásatárs Ltd. in 2020-2021.